Dismantling public education

In 2008 Clayton Christensen, Curtis W. Johnson and Michael B. Horn, through Harvard Business School, published a blueprint for the disruptive innovation of education. The plan was premised on the often repeated argument that America’s schools are failing, and that the 21st century, especially the world of technology, offered new ways to overcome, “disrupt” and ultimately replace the broken system with one that would not only make American students smarter and assure American dominance in all matters of prestige, but make a lot of HBS graduates (and of course their friends and associates) very rich in the process. Writing in the euphoria of pre-meltdown sub-prime mortgage feeding frenzy now known* as the “Great Recession (also referred to as the Lesser Depression, the Long Recession, or the global recession of 2009”) they could barely contain their excitement at the imminent demise of everything they believe stands in the way of a lucrative and rewarding educational experience: unions, tenure, and if technology delivers on all its promises, potentially that peskiest anti-learning agent of all—teachers!

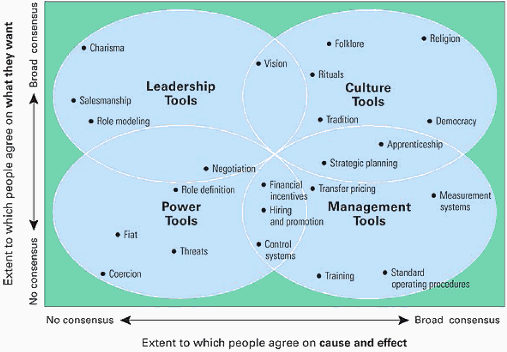

“What are “Tools of Cooperation and Change?”

Fig 1. Organizational change — Level of agreement on cause/effect vs that on solution/way forward; overlapping interests; strategies for resolution from Christensen, Johnson and Horn (2008)

“Don’t force it… just get a bigger hammer!”

According to Christensen, Johnson and Horn (2008) “Different quadrants call for different tools. When employees share little consensus on either dimension, for instance, the only methods that will elicit cooperation are “power tools” such as fiat, force, coercion, and threats” (2006, abstract). Hundreds of studies of cases falling on all points of the matrix have yielded a collection of such tools that can be used to successfully implement change. For example, sometimes people disagree because they’re trying to explain things in ways the other side can’t understand. In such a case agreeing upon a “common language” can help the parties to reach consensus. The authors rightly note that education discourse in the USA today falls in the lower left quadrant, where fiat, threats and coercion are their recommended strategies for change. “Separation” is indicated if parties’ disagreement is so fundamental they can’t compromise and can’t be coerced — dividing the conflicted parties into separate groups so they can be in strong agreement with those in their own group and remain isolated from other groups (pg. 190). But walking away is a cop out in any situation. In education especially, failure to engage from the outset is a sure sign the entire lesson will fail.

Schools, say Christensen et al., most often fall in the lower-left quadrant of the model, meaning stakeholders disagree strongly both about what they want and on what actions will produce which results. “People have tried democracy, folklore, charisma, salesmanship, measurement systems, training, negotiation, and financial incentives. All have failed. We see only three possibilities: common language, power, and separation” (Christensen, Johnson and Horn, 2008, pg. 192). It quickly becomes apparent they have no further use of the first as it may pertain to education reform. But Jeff Conklin (2006) has shown that solving problems is an iterative process. He concurs with Christensen and company that a common language is fundamental to the shared understanding that must precede transformational change, but he’s more tenacious and persistent, bringing with his stronger resolve and deeper commitment to achieving consensus a tried and true method that can be called the whip and stool of would-be wicked problem tamers. Dialogue and arguments can be mapped using successful, well documented, transparent and inclusive strategies. Just as many governments have begun to recognize (see for example Commonwealth of Australia, 2007; NCCHPP, 2012) Horst Rittel said all matters of public policy—social problems where the intersecting rights and responsibilities of multiple stakeholders might challenge an ethnographer’s skills to untangle—are “wicked problems,” and thus problems that “…are never solved. At best they are only re-solved—over and over again” (Rittel and Webber, 1973, pg. 160).

Undermining democracy

Christensen, Johnson and Horn likely wouldn’t be surprised by many of the decidedly undemocratic actions and ideas their 2008 manifesto may have inspired. But sticking only to the strategies they list, not only is it thoroughly discredited and deeply cynical to say all those methods have failed—it’s an outright, bold-faced lie.

Global Educational Reform Movement (GERM) is built on wrong premises. … GERM has acted like a virus that “infects” education systems as it travels around the world. The infection can be diagnosed by checking the state of the following five symptoms.

First is increased competition between schools that is boosted by school choice and related league tables offering parents information that helps them make the right “consumer” decisions. Second is standardization of teaching and learning that sets detailed prescriptions how to teach and what students must achieve so that schools’ performance can be compared to one another. Third is systematic collection of information on schools’ performance by employing standardized tests. These data are then used to hold teachers accountable for students’ achievement. Fourth is devaluing teacher professionalism and making teaching accessible to anyone through fast-track teacher preparation. Fifth is privatizing public schools by turning them to privately governed schools through charter schools, free schools and virtual schools.

—Pasi Sahlberg, Finnish educator

Finland is among the most commonly touted successes of financial incentives, negotiation and charisma, closer to home is Ontario, where even data-positive reformers like Michael Fullan stress the need to go beyond the agreed first step of building shared understanding to consensus. Pasi Sahlberg says “To prepare young people for a more competitive economy our school systems must have less competition.” The authors of Disrupting Class encourage attitudes and approaches that have led to the vilification and dismissal of seasoned professional teachers, union busting, and legislating various degrees of privatization in order to accomplish reform.

By eliminating public schools, as Arne Duncan and Rahm Emmanuel have been doing in Chicago, and as hurricane Katrina accomplished more effectively (and honestly) in New Orleans, disruption creates new markets. We see that notion realized in the web of for profit education networks being established by such corporate operatives within education as Michele Rhee, and nurtured and furthered from within the US Department of Education by Arne Duncan. But the grassroots group Rethinking Schools says “Chicago’s model of school closings and education privatization […] The impact of those policies includes thousands of children displaced by school closings, spiked violence as they transferred to other schools, and the deterioration of public education in many neighborhoods into a crisis situation.”

Corporate solutions in education?

Today’s business and education elite …argue that a data driven management approach to oversee teacher performance should be used to reform the education system. This approach is both naive and problematic on many levels.

After a twenty year career in business, I decided to become a mathematics teacher. … I quickly learned that teaching students was far more complicated than managing adults. Why, you may ask? There are three simple reasons that I would like to share with the business intelligentsia.

- Your employees are paid to listen to you, your students are not.

- In business, employees are selected based upon a search and interview process. Teachers do not select their students.

- In business, an insubordinate employee is fired. An insubordinate student is merely one more challenge for a classroom teacher.

Beth Goldberg, Middle School Mathematics Teacher

Alfie Kohn (1996) exposed 4 myths of competition, finding it actually undermines individual growth and development, as well as human relationships, hindering goal attainment as it enables only one party to reach the goal at the expense of others. Christensen et al. inadvertently establish the case for holistically building consensus, a process that everyone agrees takes considerably more patience and commitment. The complex stakeholder relationships even such purposeful disrupters as Christensen, Johnson and Horn cannot deny are nothing like the employer-employee relationships to which their experience is limited. This was articulated brilliantly by Beth Goldberg, a Middle School Mathematics Teacher at Linden Avenue Middle School in Red Hook, NY and quoted by Diane Ravitch here. Teachers can not fire their students, some teachers and school administrators are also parents, schools must answer the needs of many communities of practice, not just business… “Failing to recognize the “wicked dynamics” in problems, we persist in applying inappropriate methods and tools to them” (Conklin, 2010).

Conclusion

As Paul Thomas points out in this article worth reading in its entirety, “The real problem with the perpetual failure of journalism and education reporting is that credible and smart analyses of educational research is now easily accessible online—for example, Shanker Blog, School Finance 101 (Bruce Baker), Cloaking Inequity (Julian Vasquez Heilig) and the National Education Policy Center.” Connected educators, students and parents must use the Internet to avoid the biased corporate narrative, which claims schools are failing and the tools or tests they’re selling are the only cure.

Christensen and his fellow disruptors are making a category error. Not all civil services need to be hyper-efficient and bargain-basement and in a state of permanent revolution… What the institutions of a democracy should do is attend to their many disparate constituents as effectively and inclusively and openly as possible without getting creatively destroyed in the process.—Judith Shulevitz, The New Republic

Allowing corporations to lead education reform is wrong-minded from the outset. It’s completely irrational to apply Harvard Business School’s trademarked top-down disruption strategies within a sector that has no top! It’s up to students, parents, teachers, and other defenders of the Public Sphere to don safety goggles and steel-toed boots and pick up some power tools of their own. Common language and shared understanding can work both ways.

Updated: 2013-01-03. This post has been slightly edited for clarity, and to correct typos discovered after first publication. […] The (Rittel & Webber, 1973) citation was corrected: the reference was not listed but a different one, not quoted in the text, was. As the latter is available on line, rather than remove it I’ve added the link. I’ll call it ‘suggested reading.’ Updated: 2013-01-05. See Paul Thomas’s excellent suggestions for a 2014 Educators’ Agenda. [@plthomasEdD] scores EQAO Level 4 for his exemplary demo of what I mean by “donning steel-toed boots.”

§

* Quoting Great Recession From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. The script I wrote to do the drop caps strips all the other HTML from the first paragraph—my New Year resolution is to fix it using Ben Alman’s perfect solution.

Addenda and general rambling on…

Updated: I’ve also expressed similar ideas in much the same language here and here. I’ve also written about a superior approach to going beyond mere “common language,” instead using argument mapping in search of “shared understanding,” here and here. I first wrote about this book in grad school in 2009, and I acknowledged the authors’ professed concern for children’s learning, which I still have no reason to question, just as I see no contradiction†; maybe I’ve come to a deeper understanding of the solace and redemption the inherent amorality of The Market must provide its flock. Men like Christensen & Co., Bloomberg, Gates… genuinely believe they are benevolent dictators, doing good, spreading wisdom. I’ve little problem with finding and filling so-called “areas of non-consumption,” it’s their intentional and wanton creation, nearly always at public expense, that I believe must be resisted at all cost. Here I point out that Americans have always sought quality snake oil, and can discern between cunning card-sharps whom they traditionally respect, versus villainous card cheats and overdressed, know-nothing “riverboat dandies.” The difference today is too many seem willing to invite the latter back to the table. I’m calling for something quite a bit short of hanging—but let’s stop talking to the Tony Bennett/Michelle Rhee crooks and cheats, the Arne Duncan/Jeb Bush snake oil charlatans and John King riverboat dandies of education reform.

“Where-ever publick spirit is found dangerous, she will soon be seen dead.”

— Thomas Gordon, Cato’s Letter #35, 1721.

†Here’s one, although I think it’s more a case of intellectual dishonesty than inconsistency. Christensen, Horn and Johnson, somewhat apologetically almost, point to Howard Gardner’s eroded Theory of Multiple Intelligences, in part I believe to support their argument for apps in the classroom (pg. 31). They do not discuss any of Gardner’s ideas for reforming education. See Gardner, Howard (1992b) Assessment in Context: The Alternative to Standardized Testing in Changing Assessments Alternative Views of Aptitude, Achievement and Instruction, Bernard R. Gifford, Mary Catherine O’Connor, editors, Volume 30, 1992, pp 77-119. Also Gardner, Howard (1995/2011), The Unschooled Mind: How Children Think and how Schools Should Teach, 21st Anniversary edition (2011) NY: Basic Books, 322 pages. [Read online]

References:

Christensen CM, Marx M, Stevenson HH. (2006) The Tools of Cooperation and Change, Harvard Business School: Boston, USA

Christensen, Clayton; Johnson, Curtis W.; and Horn, Michael B. (2008) Disrupting Class: How Disruptive Innovation Will Change the Way the World Learns New York : McGraw-Hill

Commonwealth of Australia (2007) Tackling Wicked Problems: A Public Policy Perspective, [Archived]

Kohn, A. (1996). Beyond discipline: From compliance to community. Alexandria: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Conklin, Jeff (2005) Dialogue Mapping: Building Shared Understanding of Wicked Problems,

Conklin, Jeff (2010) Summary of available CogNexus Institute, Web site, California USA, http://cognexus.org/id42.htm retrieved 2011-10-10. Chapter 1 available as PDF http://cognexus.org/wpf/wickedproblems.pdf retrieved 2012-03-02.

Duncan, A. (1987), The values, aspirations and opportunities of the urban underclass, Boston, Harvard University

National Collaborating Centre for Healthy Public Policy (2012) Tackling Wicked Problems in the Built Environment: Of Health Inequalities and Bedbugs [Workshop details]

Oppenheimer, Todd (2003) “The Flickering Mind: Saving Education from the False Promise of Technology”, Random House. See also this Oppenheimer article, San Francisco Chronicle, Wednesday, February 4, 2009, “Technology not the panacea for education” HTML retrieved 2012-03-02

Rittel, Horst W. J. and Webber, Melvin M. (1973) Dilemmas in a general theory of planning, Policy Sciences (4) 1973, 155-169.

Rith, Chanpory and Dubberly, Hugh (2006), Why Horst W.J. Rittel Matters, Design Issues: Volume 22, Number 4 Autumn 2006 [Online versions].

Sahlberg, Pasi (2012) Finnish Lessons: What can the world learn from educational change in Finland, NY: Teachers College Press, Columbia University.

Shulevitz, Judith (2013) Don’t You Dare Say “Disruptive” It’s the most pernicious cliché of our time,blog post at The New Republic [HTML]

Smith, M. K. (2003, 2009) ‘Communities of practice’, the encyclopedia of informal education, www.infed.org/biblio/communities_of_practice.htm.nj