“Experiential learning” “Authentic learning” “multiple intelligences” “learning styles” …

Schooling

The context in which cognitive apprenticeship itself is situated deserves consideration.

We can start by considering some of the contemporaneous nomenclature: the “edubabble” of the day. Some biggies of the era are still with us today, here are four examples.

…the great waste in school comes from his inability to utilize the experience he gets outside while on the other hand he is unable to apply in daily life what he is learning in school. That is the isolation of the school–its isolation from life.

—John Dewey, 1916

quoted in Mims, 2003

The term experiential is paired with learning since the 1970s or earlier (Keeton, 1976) (Weil and McGill, 1989). Mark Smith (2001) provides a very helpful summary of the literature and reports there are two general descriptions being applied: ‘direct encounter with the phenomena being studied…’ (e.g., Borzak 1981: 9 quoted in Brookfield 1983). and ‘…direct participation in the events of life’ (Smith , 2001 quoting Houle 1980: 221). Traditional apprenticeship certainly presents us with both opportunities, but does Collins et al.s’ cognitive? I think we’ll find it does when we design for it.

Frankly, if at first simply over semantics, I’ve never been fond of the term “authentic learning.” For starters, learning is not a noun (Silvers, 2011). and I guess I’d just strive for higher precision where it’s the title of my philosophy of education. When Collins et al. use the word they refer to authentic contexts. This is not to dismiss the school of thought the name represents; practitioners who embrace the concepts and techniques seem to automatically transliterate it to enabling learning within authentic contexts., which I grant is fairly awkward. I believe it has the same meaning as situated learning, which is another term used with cognitive apprenticeship (Brown et al., 1989) (Collins et al., 1989) (Collins et al., 1991) (Lave, 1996).

In fact for many decades educators have observed a gap between life within and outside of schooling. (Dewey, 1916; Dewey, 1933; Piaget, 1974; Gardner, 1992; Boud and Miller, 1997; Mims, 2003). While my familiarity with the literature is insufficient to judge the degree to which his point “b” is true, I share an antipathy towards uncritical use of the phrase “real world” (and the advice of those who use it) with John Shindler, who warns, “…a) the real world is rarely defined by adages that include the phrase the “real world,” b) the use of the term the “real world” usually indicates a world-view that has been jaded and is fundamentally dysfunctional, and c) students are likely paying the price for it” (Shindler, 2009:Appendix J). I believe point “c” is a common destination, if by other paths, with at least one of Freire’s who, having said “…Knowledge emerges only through invention and re-invention, through the restless, impatient, continuing, hopeful inquiry human beings pursue in the world, with the world, and with each other” (Freire, 1970) said elsewhere, “The educator with a democratic vision or posture cannot avoid in his teaching praxis insisting on the critical capacity, curiosity, and autonomy of the learner.” (Freire, 1998).

The ideas of multiple intelligences (Gardiner, 1983) and learning styles (Kolb and Fry, 1975) are related. While it’s impossible to ignore their effect on teaching over subsequent decades they have naturally both been criticized at very deep levels. Again, Smith (2001, drawing on Jarvis, 1987 and Tennant, 1997) summarizes those pertaining to Kolb very well, they centre around extravagant claims and lack of empirical evidence. The latter flaw is also claimed of Gardiner’s theory, along with disconnect from findings from the field of psychology (Wellingham, 2004) (Visser, Ashton and Vernon, 2006a) (Gardiner, 2006) (Visser, Ashton and Vernon, 2006b), yet the ideas persist and some practitioners attribute successes while passionately defending their use in the classroom.

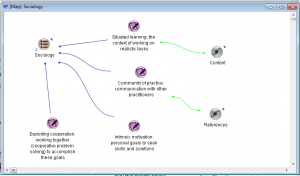

Social Anthropology’s view of Learning Communities

I strongly suspect treating cognitive apprenticeship as a framework for experience design sidesteps much of the conflict. Cognitive apprenticeship’s heritage, as the others’, traces back to activity theorists such as Vygotsky and Leontiev but charts its course via the social anthropology of Jean Lave and socially situated, community of practice-based learning she explored with Etienne Wenger (Brown, Collins, Didiuk, 1989:41 footnote 1) (Lave & Wenger, 1991) (Lave, 1996). Apprenticeship in general, and cognitive apprenticeship by design, attempts to make thinking visible, illustrated using exemplary case studies (Collins, Seely and Holum, 1991). Cognitive apprenticeship models reject models that value the results of traditionally formal learning (e.g., schooling) over informal ones (e.g., apprenticeship). From an apprenticeship perspective, the assumption that teaching necessarily precedes or is a precondition for learning, or that absence of teaching calls learning into question, is a false one (Lave, 1996:151).

Although my aim is to name specific technologies and methods for employing them that make learning visible, the perspective is that of the experience designer, the focus is on the process. The steps to enabling social interaction, placing suitable tools within reach and empowering participants to engage, according to the cognitive apprenticeship model, are quite clear.. The designer’s tasks (emphasis mine) are

- show the processes of the task and make them visible to students;

- situate abstract tasks in authentic contexts, so that students understand the relevance of the work;

- vary the diversity of situations and articulate the common aspects so that students can transfer what they learn.

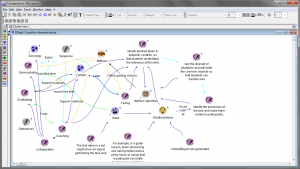

If we look within the six stages of the method—Modelling, Coaching, Scaffolding, Articulation, Reflection, and Exploration—specifically for ways to diversify participant entry and engagement, and we can turn technology on itself in effect by using polls or remote testing, for example, to question participants directly, gauge relevance on an ongoing basis, remain agile and reflexive, adjust, review, refine and revise the implementation. It may in fact end up that for some participants none of our preliminary technology picks and strategies are suitable or engaging. When we design the situation to make thinking visible we must also build into the process the ability for all participants to see and report what they’re seeing, and to maintain access to the things they need to make the experience worthwhile. This brings to the foreground an important aspect of design I’d guess is still better understood by Web designers than by most instructional designers, the separation of content and presentation. This is a concept having implications for communication (Clark, 2008) I’ll elaborate in a later instalment, but you can see a good, concise discussion of the basics by designer Sarah Horton on her site.

Summary

In the preceding paragraphs I’ve looked at the origins of cognitive apprenticeship and started to employ and apply vocabulary from the Cognitive Apprenticeship Framework. I’ve situated this framework relative to some other modern theories of learning, and we begin to see how focusing on the well-defined environment it provides—the content taught, the pedagogical methods employed, the sequencing of learning activities, and the sociology of learning—allows us to expose, nurture and tap the diversity of talent found within every community of practice. Whether we are in the role of apprentice or expert we need tools and interactions that make the processes of constructing knowledge visible and enable a variety of communication styles and media to be used between participants. I hope I have exhausted the theoretical foundation without exhausting the reader!

Next

The next instalments will start to link this theory to practice. I’ll enter from the sociology side of the environment, using social networking, but I’ll use some technology from the start. My thinking is that to find out what is being said I want to go where the discussion is taking place. Twitter is one place to start, and I have learned over time that many educators use Twitter’s “hash tag” feature to find others talking about similar things, so I loaded 24 hours worth of Tweets that contain the hash tag #edchat into Firefox, and then used the Firebug extension to get the tweets from the timeline using a Web programmers’ technique known generically (by which I mean one can take different steps using different tools to achieve the same result) as scraping?. I then removed a set of words I know are outside the scope of my investigation, and from the rest create the following “Wordle.”

Words found on Twitter #edchat from a single 24 hr period sized in proportion to frequency (www.wordle.net/create)

In my next instalment I’ll demonstrate the steps involved in creating such an image and make suggestions for researchers who might want a more robust, reliable and comprehensive approach to getting such data based on similar techniques. In so doing one important result will be an example of a technology-enhanced learning environment …in the state of emerging. I’ll further show that many if not most tools we see today stay in such emergent states indefinitely, and that by applying a framework like the one proposed by Brown, Collins, Duguid, Holum we do much more to help them reach maturity.

Comments are open and encouraged!

§

References

Boud. D. and Miller, N. (eds.) (1997) Working with Experience: animating learning, London: Routledge.

Brown, J.S., Collins, A., and Duguid, P. (1989). “Situated Cognition and the Culture of Learning.” Educational Researcher, 18(l), 32-42.

Christensen CM, Marx M, Stevenson HH. (2006) The Tools of Cooperation and Change, Boston: Harvard Business School Online http://hbsp.harvard.edu/hbsp/hbr/articles/article.jsp?articleID=R061 retrieved 2009-12-19

Clark, Dave (2007): Content Management and the Separation of Presentation and Content, Technical Communication Quarterly, 17:1, 35-60

Collins, A., Brown, J.S., and Holum, Ann (1991), Cognitive Apprenticeship: Making Thinking Visible, American Educator, [1991 reprint available on line at http://elc.fhda.edu/transform/resources/collins_brown_holum_1991.pdf accessed 2012-09-17]

Dewey, J. (1916) Democracy and Education. An introduction to the philosophy of education (1966 edn.), New York: Free Press.

Dewey, J. (1933) How We Think. A restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educative process (Revised edn.), Boston: D. C. Heath.

Freire, Paulo (1998) Pedagogy of freedom : ethics, democracy, and civic courage, Lanham, Md. : Rowman & Littlefield, 144 pages.

Freire, Paulo (1970) Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, Herder and Herder, 186 p.

Freire, Paulo (2000) Pedagogy of the oppressed, 30th anniversary ed., New York : Continuum, 184 pages.

Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of Mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. New York: Basic Books.

Gardner, H. (2006). On failing to grasp the core of MI theory- A response to Visser et al. Intelligence (34:5) 503–505

Gardner, Howard (1992) The unschooled mind: why even the best students in the best schools do not understand, [PDF]

Houle, C. (1980) Continuing Learning in the Professions, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Keeton, M. T. (ed.) (1976) Experiential Learning, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Kolb, D. A. (1984) Experiential Learning, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.: Prentice Hall. 256 pages.

Lave, Jean and Wenger, Etienne (1991). Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lave, Jean (1996). Teaching, as Learning, in Practice, Mind, Culture, and Activity (3:3) pp149-164.

Martin, Jane Roland (1982), Two Dogmas of Curriculum, Synthese, Vol. 51, No. 1, Questions in the Philosophy of Education (Apr., 1982), pp. 5-20

Mims, Clif (2003), Authentic Learning: A Practical Introduction & Guide for Implementation, Meridian: A Middle School Computer Technologies Journal, Volume 6, Issue 1, Winter 2003, Raleigh, NC: NC State University, http://www.ncsu.edu/meridian/win2003/authentic_learning/ retrieved 2012-10-10.

Piaget, J. (1974). To understand is to invent: The future of education. New York: Grossman.

Shindler, John V. (2009), Appendix J: Examining The Use of the Term the “Real World” of School, College of Charter School of Education, web page associated with the book “Transformative Classroom Management,” Hoboken: Jossey-Bass, 384 pages.

Silvers, Aaron (2011) Fundamental Design of Learning Activities, blog post http://www.aaronsilvers.com/2011/02/fundamental-design-of-learning-activities/, retrieved 2011-08-10.

Smith, M. K. (2001). ‘David A. Kolb on experiential learning’, the encyclopedia of informal education. Retrieved [enter date] from http://www.infed.org/b-explrn.htm.

Visser, Ashton and Vernon, 2006a Beyond g: Putting multiple intelligences theory to the test, Intelligence (34:5) 487–502

Visser, Ashton and Vernon, 2006b g and the measurement of Multiple Intelligences: A response to Gardner, Intelligence (34:5) 507–510

Weil, S. Warner & McGill, I. (eds.) (1989) Making Sense of Experiential Learning. Diversity in theory and practice, Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

Willingham, Daniel T. (2004), Reframing the Mind: Howard Gardner and the theory of multiple intelligences, Education Next, Vol. 4, No. 3 http://educationnext.org/reframing-the-mind/ retrieved 2012-10-10.

The past 30 years in education research has seen the influx of big ideas from computer science, social anthropology, design and even architecture. We now say learning is situated in authentic social contexts many call communities of practice.

The past 30 years in education research has seen the influx of big ideas from computer science, social anthropology, design and even architecture. We now say learning is situated in authentic social contexts many call communities of practice.